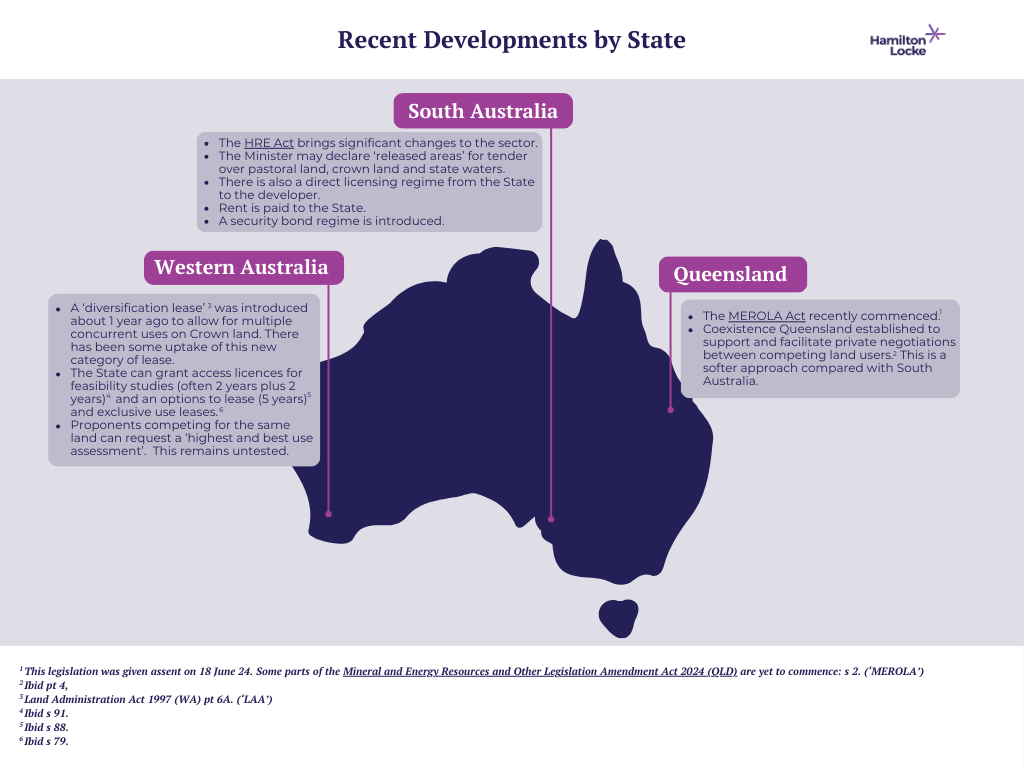

Competing land use and securing tenure for projects on crown land continue to be key issues in early stage development of renewables projects. States are adopting different policy approaches to this issue and this will be a key policy area to evolve over the next 5 years. The issue is particularly important in the resource rich states of South Australia, Queensland and Western Australia in which renewables projects compete with mining projects, carbon projects and pastoral use. Native title holders also have existing rights and interests over large parts of crown land in those States.

In this article, we compare the recent initiatives in South Australia and Queensland with the framework in Western Australia which commenced about 1 year ago.

South Australia

SA Government takes an active role, also includes private negotiation

The Hydrogen and Renewable Energy Act 2023 (SA) (HRE Act)7 aims to ‘facilitate the grant of licences that enable hydrogen and renewable energy projects to co-exist, so far as possible, with other land uses’.8

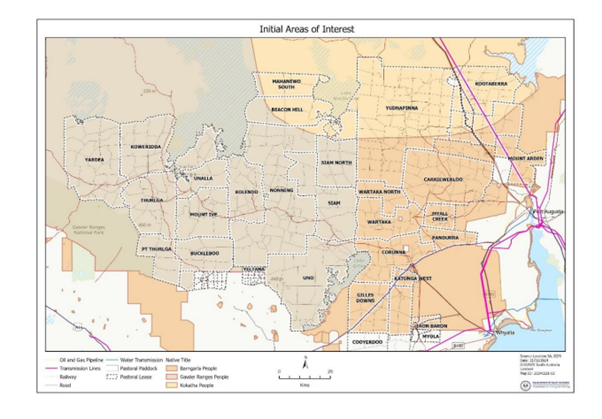

The SA Government has identified areas as potential ‘release areas’9 which will be open to competitive tender. Currently, the areas of highest stakeholder interest and viability include the Gawler Ranges, Upper Eyre Peninsula and Upper Spencer Gulf.10

Source: Release Areas – Consultation Draft on Hydrogen and Renewable Energy Regulations Information Sheet, p 3. (undated, released in the context of consultation on the regulations)11

Some of the key features of the HRE Act are:

- Tender for optimal land: The introduction of a competitive tender process for ‘release areas’. The release areas will generally be pastoral land, crown land or state waters where large-scale wind and solar resources can be developed.

- New licensing regime:12 There is a new licensing regime in which the State grants licences directly to developers that authorise certain activities:

- Rent is payable directly to the State on ‘Designated Land’ and on a special enterprise land13 (instead of rent being payable to the pastoral leaseholder). Owners may be entitled to compensation through access agreements. Designated Land is pastoral land, crown land or state waters (with exceptions for national parks/marine reserves).

- Available licences include:

- Renewable Energy Feasibility Licence – to conduct feasibility activities;

- Renewable Energy Infrastructure Licence – authorising the construction and operation of renewable energy infrastructure (term is 50 years – or another term the Minister determines); and

- Associated Infrastructure Licence – authorising ancillary infrastructure for storage and transmission.14

- A Special Enterprise Licence (SEL) may be granted if the project is of major significance to the State economy and must be ratified by the Governor.15

- The process to grant an SEL is more onerous and expensive as it provides the licensee with a right to enter and use freehold or crown land. It comprises two stages:

- Concept Phase – Prior to applying for an SEL, a proponent must apply to consult with the Minister. Before agreeing to consult with the proponent, the Minister:

- may consult with relevant owners (including any native title claimant); and

- must be satisfied that the proponent has taken reasonable steps to obtain consents from the relevant owners.16

- A proponent may only apply for an SEL if the Minister consents to the proponent doing so after the Concept Phase. The Minister must consult with the owners when considering the application.

- Concept Phase – Prior to applying for an SEL, a proponent must apply to consult with the Minister. Before agreeing to consult with the proponent, the Minister:

- An owner cannot object to the entry of a SEL However the owner:

- is entitled to compensation for any economic loss, hardship or inconvenience they suffer in consequence of authorised operations.17

- may apply to the Environment, Resources, and Development Court (ERD Court) for an order for the licensee to acquire the owner’s interest in the land at market value if the licensed activity substantially impairs the owner’s use and enjoyment of the land and compensation for disturbance.18

- Access agreements: Unless an SEL is granted, a developer must enter into an ‘access agreement’19 with the owners of the land prior to commencing operations.

‘Owners’ include registered interest holders, occupiers, native title holders, pastoralists, persons holding resource tenements, holders of an aquaculture lease or any persons prescribed by the regulations.

Negotiations follow this framework:20

- All parties must negotiate in good faith. If negotiations do not reach a resolution within a specified timeframe, the Minister may intervene to mediate, or the matter may be escalated to the ERD Court.

- Compensation is assessed by reference to the economic loss, hardship or inconvenience suffered by the owner because of the developer’s operations.

- Any access agreement entered into will bind successors in title to the parties of the agreement and all subsequent holders of a licence to which the agreement relates.

- Bond and security regime: The Minister may require a licensee to provide a bond for liability during operations and rehabilitation.21 We suggest that developers bear this new statutory requirement in mind in negotiating indemnities and remediation/decommissioning clauses in options and leases to avoid duplication of obligations/liability.

This model echoes the Queensland system of Conduct and Compensation Agreements.22 However, a key difference is that the system provides for the licensing system directly from the State, putting proponents on a better footing to negotiate with other interest holders.

Queensland

‘Coexistence Queensland’ – emphasis on private rights and negotiation, no specific renewables tenure from the State

The Mineral and Energy Resources and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2024 (Qld) expanded the roles of institutions to support co-existence between stakeholders .23 For instance:

- The remit of the Gasfields Commission Queensland (renamed as Coexistence Queensland) has been expanded to include the renewables sector.24 Its role is to facilitate relationships, act as a central point of contact, advise the minister, partner with entities and publish resources rather than determine, decide or intervene.25

- The Land Access Ombudsman’s functions now include investigating breaches of access agreements and providing alternative dispute resolution services for parties negotiating make good agreements, conduct and compensation agreements, and other access agreements.

In addition, Queensland has recently enacted legislation for Renewable Energy Zones through Part 6 Energy (Renewable Transformation and Jobs) Act 2024 (Qld).26

These recent legislative changes follow policy papers and plans over recent years including The Queensland Resources Industry Development Plan27and the Renewable Energy Zone Roadmap.28

The emphasis in the amended legislation remains on private negotiation between the parties for access and compensation through Conduct and Compensation Agreements (CCA) and the mandatory provisions of the Land Access Code.29 CCAs offer limited certainty for early stage renewables proponents during an option period, especially if a CCA is already in place, as an option-holder is unlikely to be a ‘landholder’ and does not have rights to negotiate at this stage.

There is no specific category of leasing or licensing from the State for renewables projects.30 Instead, typically the proponent negotiates for a sublease or licence from the pastoral lease holder – Ministerial consent can be sought for the production of renewable energy to be added as an additional purpose to the lease.31

Western Australia

Diversification Leases permit concurrent use, private negotiation with the highest and best use circuit breaker

A new category of lease on crown land called a ‘diversification lease’ was introduced approximately 1 year ago.32 Diversification leases grant non-exclusive tenancy, allowing for multiple concurrent uses and co-existence with certain mining tenements and native title rights.

This tenure is the State’s preferred approach for large scale wind and solar projects due to the size of the land required for those projects. Diversification leases can be used in conjunction with exclusive tenure for specific infrastructure.

The Minister may grant a diversification lease by private treaty or competitive process.33 An option to lease may be granted which includes conditions precedent to the grant of a long-term lease tenure. The conditions precedent can include negotiation and registration of an Indigenous Land Use Agreement, approval of the Minister for Mines under section 16(3) of the Mining Act 1978 (WA), and obtaining planning and environmental approvals.

The tenure pathway in WA is somewhere between the South Australian and Queensland system.

- Like South Australia, the Minister may grant directly to proponents licences, options, and leases for renewable and hydrogen projects. There is no need to take an access licence or sublease from the pastoral lease holder.

- Like Queensland, the framework prefers parties to negotiate privately on co-existence arrangements. By comparison, CCAs in Queensland give rights to existing owners and occupiers to negotiate compensation from mining parties for access (rather than shared use specifically). In WA, negotiations between private parties can be supported by the Senior Officers Group.34

- In WA, there is a distinction between co-existence arrangements at the feasibility stage (eg sharing of infrastructure) and at the implementation stage when constructed and operational – at this later stage exclusive lease tenure may be needed for some infrastructure.

The WA framework also includes a third party circuit breaker. The ‘highest and best use assessment’ policy allows the Senior Officers Group to assess the highest and best use if more than one proponent expresses an interest in the same land and cannot reach an agreement. The policy is developed in relation to hydrogen projects but we understand it can also be applied to renewables projects.35

This ‘highest and best use’ mechanism has the potential to be a useful pathway for renewables proponents with competing proposals but as far as we are aware this mechanism is currently untested.

Proponents will be cautious in adopting this mechanism – there is always risk in any mechanism that sends control of the outcome to a third party and negotiation will be a preferred first pathway.

Final thoughts

Competing land use remains a difficult issue. Governments need to balance the interests of traditional landowners, resources parties, carbon project proponents, pastoralists and renewables and hydrogen proponents. Without tenure certainty for renewables and hydrogen proponents at an early stage, proponents will be hampered in investment and finance decisions. States that have clear frameworks to ensure that tenure certainty is available early in project will see faster development of projects and more investment.

1This legislation was given assent on 18 June 24. Some parts of the Mineral and Energy Resources and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2024 (QLD) are yet to commence: s 2. (‘MEROLA’)

2Ibid pt 4,

3Land Administration Act 1997 (WA) pt 6A. (‘LAA’)

4Ibid s 91.

5Ibid s 88.

6Ibid s 79.

7The HRE Act commenced on 11 July 2024.

8Hydrogen and Renewable Energy Act 2023 (SA) s 3(j). (‘HRE’)

9Ibid s 10.

10Government of South Australia, ‘Consultation on draft Hydrogen and Renewable Energy Regulations’, Hydrogen and Renewable Energy Act (Information Sheet) p 3 <https://www.energymining.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/989333/Release-areas-information-sheet.pdf>.

11Department of Energy and Mining, ‘Hydrogen and Renewable Energy Regulations 2024’, Release Areas (Web Page) p 3 <https://www.energymining.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/989333/Release-areas-information-sheet.pdf>.

12Ibid General Licensing and Permits <https://www.energymining.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/989330/General-licensing-and-permits-information-sheet.pdf>.

13HRE (n 7) s 45.

14Ibid pt 4.

15Ibid s 26.

16Ibid.

17Ibid s 79.

18Ibid s 81.

19Ibid s 41.

20Ibid s 42.

21Ibid s 43.

22Mineral and Energy Resources (Common Provisions) Act 2014 (Qld) s 43.

23Department of Resources, The MEROLA Amendment Act Explained (Web Page) <https://www.resources.qld.gov.au/qridp/actions/action-updates/the-merola-act-explained>.

24Coexistence Queensland, About us (Web Page) <https://www.cqld.org.au/about-us/>. (‘Department of Resources’)

25MEROLA (n 1) s 16.

26Legislative assent 26 April 2024: Energy (Renewable Transformation and Jobs) Act 2024 (Qld).

27Queensland Government, Queensland Resources Industry Development Plan (Web Page, June 2022) p 29 <https://www.resources.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/1626647/qridp-web.pdf>. This plan outlined the government’s commitment to creating a clear framework for coexistence and updating regional plans to capture the changing and competing demands for land use (some of which pre-date the emergence of the renewable energy industry).

28This Roadmap (updated in March 2024) does not address conflicting land use in any detail but envisions that these conflicts would be managed as part of the process of identifying Renewable Energy Zones.

29The Queensland system also includes a ‘Deferral Agreement’ and an ‘Opt-out Agreement’.

30There is a lease of Crown land available for a significant development – Land Act 1994 (Qld) s 129 (‘Land Act’).

31Ibid s 154.

32LAA (n 3) s 92B.

33Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage, ‘Policy Framework’, Guiding the use of Diversification Leases on Crown land under the Land Administration Act 1977 (Web Page) p 2 <https://www.wa.gov.au/system/files/2023-08/policy-framework-diversification-leases.pdf>.

34The Senior Officers Group comprises officers from officers from Department of Planning Lands and Heritage (DPLH), the Department of Mines, Energy, Industry Regulation and Safety (DEMIRS), and the Department of Jobs, Tourism, Science and Innovation (JTSI).

35Western Australian Government, ‘Western Australian Renewable Hydrogen Policy: consideration of highest and best use’, Policy: Process for managing competing projects proposed for the same area of land’ (Web Page) p 2 <https://www.wa.gov.au/system/files/2022-12/221205_RenewableHydrogen-Policy_DIGITAL.pdf>. This policy was published in 2022 and contemplates updates to reflect the amendments introducing diversification leases.