Mindfulness in simple terms is when you are aware and attentive, focused in the present moment, rather than being on auto-pilot.[1] An important component of mindfulness is being detached from your emotions and ensuring that you do not allow pre-judgment of the events or people involved to interfere in the moment. It is “a heightened state of involvement and wakefulness”.[2]

You can practice mindfulness by ensuring you live in the moment; that you are present when talking with friends, family and colleagues; that you take time out to quiet your mind by being in nature (such as hiking or going to the beach), engaging in hobbies (such as golf, surfing), meditation, prayer, yoga or listening to music.

Mindfulness can allow you to be incredibly attentive and productive; it enhances emotional regulation; drives cognitive clarity and reduces stress. It is not just for new-age hippies, many successful entrepreneurs, athletes, politicians and artists practice mindfulness, including meditation.

What is mindfulness?

“ At the very highest levels of any field – Fortune 50 CEOs, the most impressive artists and musicians, the top athletes … you’ll find mindful people, because that’s the only way to get there.”

– Ellen Langer, Harvard Professor of Psychology[3]

Mindfulness as a discipline is a combination of psychology, neurophysiology, and ancient Buddhist traditions. It is when you are aware and attentive, focused in the present moment, abandoning pre-conceived ideas and being emotionally detached.[4]

According to Boyatzis and McKee, “Mindfulness is the capacity to be fully aware of all that one experiences inside the self – body, mind, heart, spirit – and to pay full attention to what is happening around us – people, the natural world, our surroundings and events.”[5]

There is unfortunate cultural baggage associated with mindfulness and meditation, particularly with self-professed gurus promising enlightment, near-magical self-healing and other cosmic woo-hoo. Park your skepticism and explore this powerful concept further.

A common misconception is that mindfulness is exhausting and stressful with all that focused thinking. To the contrary, the most exhausting and stressful thing to do is uncontrolled thinking, the endless negativity, emotional over-reaction and worrying about the future and the past.[6]

Martin Luther once said, “I have so much to do today, I’ll need to spend another hour on my knees.” To him the meditative power of prayer was an important source of energy.

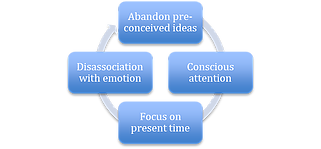

Mindfulness is made up of four interrelated elements:

Disassociation from emotion: The core of this element of mindfulness is to be detached from your feelings, thoughts and emotions with a sense of self-control. This is not about repressing your emotions but rather to experience them as they occur.

Remember the mantra: “I am not my thoughts”. They happen within you but you need to be consciously aware that they are simply your thoughts and do not define you. Don’t let your mind be bombarded by uncontrolled emotions or thoughts.[7] Everyone will experience negative feelings and thoughts such as hate, anger, guilt, shame, despair. To be mindful requires you acknowledge that thought, then consciously detach from it.

Abandon pre-conceived ideas: This element of mindfulness requires that you do not allow pre-judgment to interfere in the moment. Attempt to experience every moment without any pre-conceived views and just accept the moment for what it is. It means considering each moment as being unique and different (rather than assuming it is simply the same as previous ones). You need to approach each experience with a sense of curiosity and openness.[8] Seigel argues:

“This distinction between [mindfulness] and just paying attention with preconceived ideas that imprison the mind … is the difference that makes all the difference.”[9]

Focus on the present time: Mindfulness requires focus on the present time, and that you are not distracted by the past or the future. If you focus on past events you may be prevented from fully experiencing the present. Your mind will automatically try to categorise and label an event and the people or issues involved, immediately limiting your capacity to experience the event as it really is. As soon as you pigeon-hole someone, such as “She is inflexible. He is arrogant”, then you automatically limit your relationship.[10]

Conscious attention: To cultivate mindfulness it is important to minimise automatic, unconscious or mindless behaviour. With basic tasks like polishing shoes or eating breakfast there is little harm in being on “auto-pilot” but it is problematic to live your life that way. If you consider each moment as being new, unique and worthy of attention, you realize we simply have moments to live.[11]

A danger is when you engage in rule-based behaviour. This is when you perform tasks using checklists, rules, routines or precedents without really thinking about the issues or exploring alternatives. Checklists and rules should be a rough guide only but don’t allow them to constrain you or use them mindlessly.

A classic example is in aviation, where pilots mindlessly go through the take-off protocols – flaps up, throttle on and anti-ice off. But if it is snowing or the weather is closing in, turning anti-ice off will crash the plane. Better if the list requires you to be present and mindful. They need to ask qualitative questions, so “Check weather conditions. If weather is fine, turn anti-ice off.”[12]

Another example is that of a police officer who had trained over and over again to disarm a criminal holding a pistol. The officer had practiced the drill with his partner literally hundreds of times. You twist the gun away from the offender, pointing it away from you but at the end of the drill you hand the pistol back to your partner so you can practice disarming again. The officer successful disarmed the offender who was holding up a service station but immediately handed the pistol back (like he did in training with his partner).

Why practice mindfulness?

“If you are depressed you are living in the past. If you are anxious you are living in the future. If you are at peace you are living in the present.”

-Lao Tzu, Chinese philosopher

There are numerous benefits to mindfulness. Your performance will improve. You will find it easier to pay attention and for longer. You are more creative, less stressed and more balanced emotionally. An unexpected benefit is that you tend to like other people more (because you are not as judgmental or evaluative) and accordingly people like you more in return.[13]

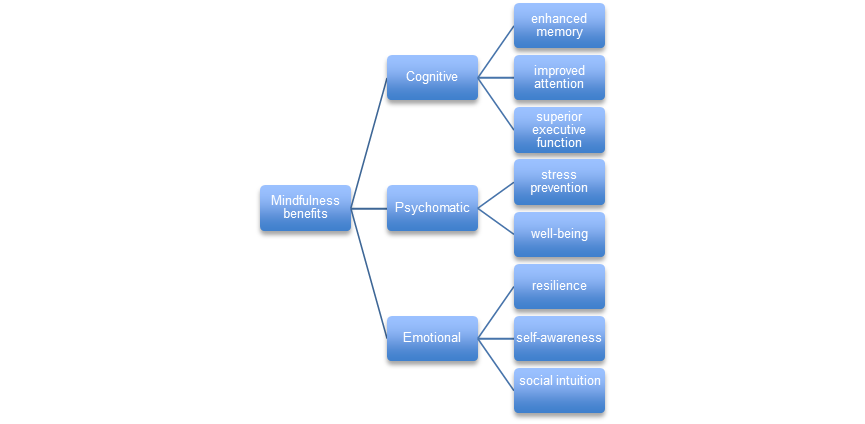

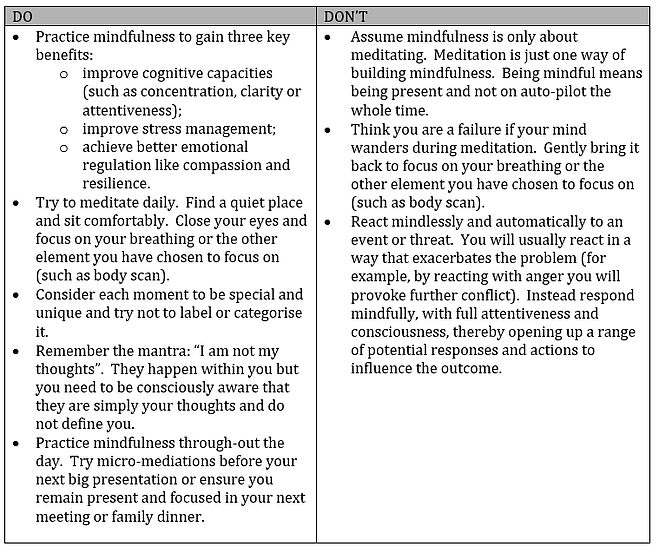

Mindfulness helps us across three main dimensions[14]:

Cognitive: improve cognitive capacities (such as concentration, creativity or attentiveness)

Pyschomatic: to improve stress management and overall wellbeing

Emotional: to achieve better emotional regulation

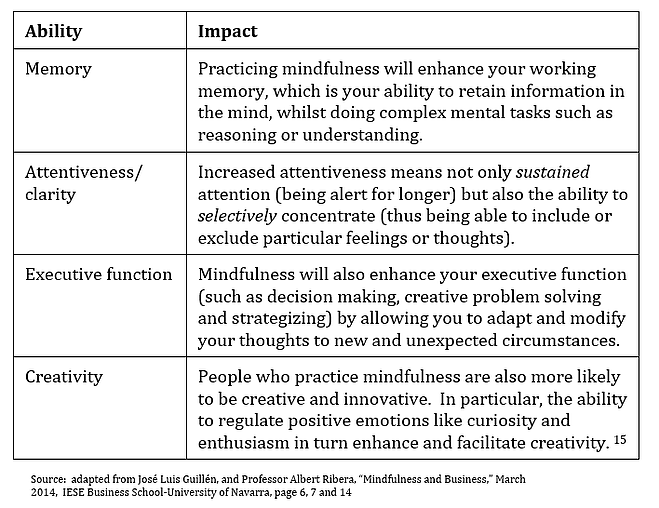

Cognitive abilities

The first benefit of mindfulness is improved cognitive abilities:

Psychomatic

“We can’t change the obstacles that life puts in our way, but we can change how we react to them.”

Mindfulness is a powerful tool for preventing and managing stress.

We need some stress to perform. We need deadlines and to be pushed out of our comfort zone to grow and learn. Stress is part of our natural fight-or-flight mechanism and is essential for survival.

Effectively there are two types of stress, positive stress (called eustress) and negative stress (called distress). Eustress is healthy and necessary for performance and drives fulfillment.

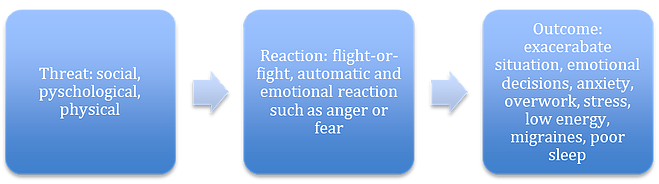

Distress is when there is a “red alert” type reaction to physical, social or psychological challenges or threats (real or perceived) that you cannot manage or resolve through adaptation or other forms of response.

Most techniques for managing stress revolve around external factors, such as seeking balance, getting sleep, avoiding coffee, planning regular breaks or playing sport.

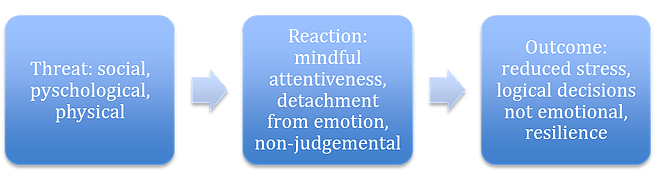

Mindfulness techniques focus on internal aspects. So rather than trying to change the external stressor, it instead focuses on trying to change how you perceive and experience that stressor. In particular, to change your experience of the negative event by training your mind through cognitive attentiveness and practicing disassociation or detachment from emotion, abandoning pre-conceived judgment and the ability to selectively focus.[15]

You can experience the same event in completely different ways. You can react mindlessly and automatically, usually in a way that exacerbates the problem (for example, by reacting with anger you will provoke further conflict). Alternatively you can respond mindfully, with full attentiveness and boost your consciousness, thereby opening up a range of potential responses and actions to influence the outcome.

It is about seeing the turmoil arising from your instinctive reactions for what they are: emotions and feelings. Remember the mantra from the previous section: you are not your thoughts. So instead of reacting blindly to an event or stressor, focus on the outcome you want to achieve and then the best reaction to achieve that outcome.

We all have a natural tendency to over-think potential scenarios and worse still exaggerate the downside. We think a certain thing is going to happen (eg, “I am going to lose my job because I stuffed up the Peterson account”) and that when it does the results is going to be terrible, catastrophic (eg. “I will be unemployable, have to sell my house, and will die lonely and broke in a homeless shelter”).

Next time you catch yourself mindlessly worrying about something, remind yourself that you cannot possibly know what is going to actually happen. Then think of four or five reasons why that thing isn’t going to happen (eg, Peterson has been your client for 10 years, the firm values you and won’t over-react, you still have time to fix the stuff up etc). Then think of four or five reasons that even if you did lose your job, the upsides (eg, plenty of other places would hire you, it would give you more time to travel or see your family, etc.)[17]

There have been various other studies that show mindfulness can be a useful tool for managing stress, reducing its side effects (such as anxiety, sleeplessness, hyperactivity, depression) and improving overall well-being.[18]

Emotional

Another important benefit of mindfulness is improvements in your ability to regulate your emotions, and in turn, better intuition, self-awareness and resilience. This section also looks at improved charisma and the neuro-science supporting the links between emotional regulation and mindfulness.

Emotional regulation: Some of the key aspects of emotional regulation are:

-

Resilience: ability to deal quickly with situations and associated emotions, such as blocking anger or other negative emotions.

-

Outlook: ability to make positive emotions and energy last.

-

Intuition: the ability to read other peoples tone and body language.

-

Self-awareness: being aware of your own emotions and feelings.

Emotional intelligence is your capacity to control and express your emotions and to also empathetically manage interpersonal relationships and influence others. Recent research has shown that emotional intelligence is an important attribute shared by high performing managers and the most significant differentiator between successful leaders and average ones.[19]

In his book “Emotional Intelligence”, Daniel Goleman suggests that EQ (or emotional intelligence quotient) might actually be more important than IQ (intelligence quotient). So if you have two people with the same or similar IQ, the one with the EQ is more likely to be successful – they can read social situations better, control their anger better, sustain positive energy for longer and understand other people’s emotions and drivers better.

Research carried out by the Carnegie Institute of Technology shows that 85 percent of your financial success is due to skills in “human engineering,” your personality and skills in negotiation, leadership and communication. Technical knowledge only accounted for 15 percent of financial success.[20]

Some studies in relation to EQ[21]:

-

Nobel Prize winning psychologist, Daniel Kahneman, found that people would rather do business with a person they like and trust, even if that person is offering lower quality or a higher price.

-

An insurance company found that sales agents who had weaker emotional competencies (such as self-confidence, initiative, and empathy) only sold policies with an average premium of $54,000. Agents who scored higher, sold policies worth more than double the premium, with an average of $114,000.

Mindfulness helps strengthen your emotional regulation. In a practical sense the art of being mindful is ensuring you control your emotions, remain detached and in control. It stops you from getting weighed down with negativity and minimizes the risk of wasting excessive energy and time on endlessly mulling over issues, rehearsing conflicts and wallowing in depression, anxiety or rage. There are studies that show practicing mindfulness modifies and strengthens your emotional style (see below). In other words you can improve your EQ through practicing mindfulness.

Charisma: Another benefit of mindfulness is that you tend to like other people more, because you are not as judgmental or evaluative, and accordingly people like you more in return. In other words, your charisma is increased.

A recent study on gender roles supported the charismatic effect of mindfulness.[22] Woman face a dilemma, in that if they act in a strong more masculine way they are seen as “bitchy”. However, if they act in a softer more feminine way, they are seen as weak and not leadership material. Langer asked a group of woman to give a persuasive speech, some to do in a masculine way, others in a feminine way. She asked half of each of those groups to also give their speech mindfully. Audiences preferred the mindful speaker, irrespective of which gender role they were playing.

Neuro-science: Research by Davidson has shown critical relationships between neural connections, neurochemistry and our emotional style. He concludes that mindfulness trains the brain by tapping into the plasticity of the brain connections and can actually alter patterns of brain activity, that in turn reinforces compassion and empathy.[23]

In terms of brain function, the amygdalae (lizard brain) regulates negative emotional responses like fear, sadness and anger, which are necessary for survival. The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is part of the rational brain.

The left PFC (LPFC) sends inhibitory messages to the amygdalae, signaling it to calm down. Davidson discovered that people who are emotionally resilient have strong connections between the LPFC and amygdalae. As a result of that strong connection, the negative emotions generated by the amygdalae are calmed down, and you don’t get bogged down in negativity.[24] Conversely, those with limited emotional resilience have less signals and weaker connections between the LPFC and the amygdalae.

To increase resilience you need to strengthen the LPFC, so it sends more and stronger signals to the amygdalae. Two potential therapies to do this are:

-

There is a type of meditation where you objectively observe your thoughts and feelings as if you were an unbiased and non-judgmental witness. Davidson argues that this type of mental training gives you “the wherewithal to pause, observe how easily the mind can exaggerate the severity of a setback, note that it as an interesting mental process, and resist getting drawn into the abyss”.[25]

-

Cognitive reappraisal is a practice where you challenge negative or catastrophic thoughts (such as “I’m going to get sacked” or “I am hours behind in my work”).

How to practice mindfulness?

You can practice mindfulness by ensuring you always live in the present moment, including:

-

Meditation

-

Being present

-

Chores

-

Quiet time

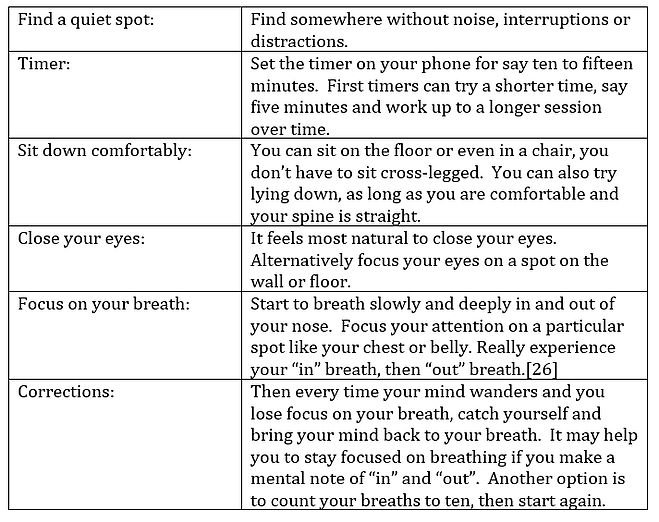

Meditation

The primary mechanism through which meditative mindfulness is produced is by practicing attentiveness. Focusing your attention on a single element, usually breathing or a bodily element. When your mind wanders from your breathing or the other element you have chosen to focus on (such as a body scan), you need to pull your attention back to your breathing or the other chosen element. Over time your focus will become more stable and distractions less frequent.

There are many different ways to meditate, however the basic components are:

The first few times you try to meditate your mind is likely to jump between different ideas, thoughts and feelings. You are not alone, everyone’s mind is racing. An out-of-control jumble of ideas, thoughts, emotions, to-do-lists, fantasies, doubts, worries, ambitions. Even experienced meditators can be distracted.

The art is to catch yourself when your mind starts wandering and then (without judging yourself) and gently bring your focus back to your breath. “Beginning again and again is the actual practice, not a problem to overcome so that one day we can come to the ‘real’ meditation.”[27]

In the same way as doing arm curls or a bench press strengthens your arms or chest, the practice of bringing your mind back into focus will strengthen your attention muscle.

Being present

How often have you been in a meeting when the other person is not really paying attention? They are not truly engaged, seem agitated and are not really listening. They are distracted by text messages or incoming emails.

Similarly, how often are you personally not really present and in the moment on a telephone call or in a meeting? How often are you having dinner with your family or friends but you are distracted by the television in the background or simply caught up in your own thoughts?

Not only is the lack of attentiveness rude but you are not making the most of the opportunity. If it is a business call then you are unlikely to have absorbed all the important information being conveyed. If its family time, you have missed the opportunity to genuinely bond with your children or spouse. There is more to quality time with family than just being home. If you are constantly checking messages, taking phone calls or thinking about work then you are not enjoying your family and you are also not giving your brain the down time it needs.

Do your best to ensure that you are really present when talking with friends, family and colleagues. Bring all your focus and attention to the current conversation. Don’t let your mind focus on internal chatter about emotions, feelings, jobs to be done. Don’t think about the past (the promotion you missed out on or argument you had with a work colleague yesterday) or future (the big client pitch tomorrow or project deadline next week), just be present in the here and now. As with the meditation practice in the section above, if your mind wanders just gently bring it back to the present moment and focus on the conversation.

You might have to bring your mind back dozens of times in a single meeting. This is part of the practice of mindfulness. This will help re-wire your mind to be able to maintain attentiveness for longer periods.

Chores

“ Before enlightenment chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood, carry water”

– Zen Buddhist saying

You can use any simple daily chore or activity (brushing your teeth, walking up stairs, sweeping/vacuuming the floor, gardening, doing the dishes etc) and incorporate into your mindfulness practice.

Before you start the activity, take three deep breaths. Let your mind focus on the breath and nothing else. Ensure you are completely focused on the present moment. Then slowly and deliberately undertake the chosen activity. Think only of the activity and be aware only of the senses involved. Don’t let your mind wander. Gently bring your mind back to focus on the task.

I find it extremely easy to be mindful when doing manual work at our farm, like fixing broken fences, chainsawing fallen trees, working on a tractor, mustering cattle on horse back or doing yard work with cattle. There is inherent risk in many of these tasks and if you let your mind wander you are likely to get seriously hurt: thrown off a horse, charged by a bull or cut by the chainsaw etc. A few hours of this manual work and your mind is re-set, I am calm and problem solving becomes easier.

Quiet time

You can help yourself achieve mindfulness if you give yourself quiet time, peaceful moments every day to tune in to yourself. There are certain activities which help calm your mind (particularly if done by yourself), including:

-

being in nature (such as hiking, sailing, visiting the country or going to the beach);

-

doing crafts (such as sewing or knitting);

-

engaging in hobbies or sports (such as gardening, bike riding, golf, tennis, surfing or fishing);

-

drawing, painting or creative writing;

-

yoga;

-

dancing, reading or listening to music.

All these activities tend to ensure you are in the moment. When undertaking them they are absorbing and intrinsically rewarding, you are not worrying about work, mulling over recent or impending arguments, juggling endless to-do-lists. Being outside and active should hopefully re-set your brain and wash-away your stresses. If you find your mind wandering to think about things (worries, stresses, fears, tasks to be done) other than the chosen activity (whether it is hiking, biking or otherwise) then gently bring your mind back to the present moment.

Another activity for mindfulness is yoga. There is something inherently calming about the practice of yoga, as you need to focus on your positions and holding them. Experienced practitioners know that the discomfort will pass. They report that afterwards they feel very calm, centered and peaceful. This state of peacefulness can last for many hours afterwards.

Exercise

The next time you are in a meeting or conference call, try the following mindfulness exercise.

Firstly, instead of letting your mind wander, keep focused on the moment. Don’t think about yesterday (such as the argument you had with your boss) or the future (such as the presentation you need to write and rehearse for tomorrow), just think about the meeting and the people and issues involved. When your mind gets distracted, bring it back gently to the meeting.

Second, try to listen non-judgmentally. Don’t allow any pre-conceived views to interfere with the moment and just accept it for what it is. Avoid the temptation to categorise the event as the same as a previous one (for example, “this is just like the meeting I had last year with the English supplier”). Also don’t pigeon-hole people with your previous perceptions (such as he’s arrogant or she’s inflexible).

Third, don’t react emotionally to the situation. Instead focus on the outcome you want and the best way to achieve it. If your instinctive reaction is to react angrily to an insult or dismissively to a naïve comment, rein yourself in and focus on the result you want first.

When I first tried this exercise I found it hard to stay in the present moment. My mind kept jumping to think about what was next in my diary or trying to resolve unrelated issues. I was constantly churning through my to-do-list, as if my mind would forget the tasks if I didn’t keep noting them. I was also tempted to check emails or text messages on conference calls, trying to multi-task, as if I was being efficient by doing extra tasks. The problem was my mind wasn’t 100% on the call and I wasn’t absorbing all the information or properly reading the tone of the call.

Mentally churning through a to-do-list is a common issue for many people. It can be quite stressful and distracting (particularly at bedtime). The trick here is to keep a fail-safe system so your brain can relax, knowing that you aren’t going to forget. There are a range of good reminder tools (like an app on your iPhone) where you can record the task, when it is due and set a reminder based on either time or place. Another strategy is to tell yourself to trust that the brain will remind you later.

By being completely attentive I noticed that I started to get a far deeper feeling for all the issues, my recall of the meeting became better and I was also picking up on subtle signals (for example, the negotiator on the other side hesitated slightly when they asked for a particular point, as if they knew it was an ambit claim).

The harder aspect was trying not to pre-judge the meeting. When you have sat through dozens of negotiations, it is easy to think you have seen it all, that you have a standard response to every challenge or issue. You think you have seen all these strategies and tricks before and can combat them with your own standard toolbox of negotiation techniques.

Summary

In summary, some key strategies for practising mindfulness:

About the author

Nick Humphrey is the managing partner of Hamilton Locke. He is the Chairman of the Australian Growth Company Awards and author of a number of best-selling books on business and leadership. His latest book is Maverick Executive: strategies for Driving Clarity, Effectiveness and Focus, published by Wolters Kluwer.

[1] José Luis Guillén, and Professor Albert Ribera, “Mindfulness and Business,” March 2014, IESE Business School-University of Navarra, page 3

[2] Langer, E. J., and M. Moldoveanu (2000), “The Construct of Mindfulness,” Journal of Social Issues, 56(1), pp. 1-9

[3] Alison Beard, “Mindfulness in the age of complexity,” Harvard Business Review, March 2014, page 4

[4] Jon Kabat-Zinn, “Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Context: Past, Present and Future,” 2003, American Psychological Association

[5] Richard Boyatzis, Annie McKee, “Mindfulness: an essential element of resonant leadership,” Harvard Business School Press, 2007, page 2

[6] Beard, “page 4

[7] Guillén, and Ribera, IESE, page 5

[8] Bishop, S. R., et al. (2004), “Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition,” Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, page 11

[9] Seigel, D.J, “The mindful brain reflection and attunement in the cultivation of well-being,” 2007, W. W. Norton & Company, as referred to in Guillén, and Ribera, IESE, page 4

[10] Beard, page 5

[11] Jon Kabat-Zinn, “Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness,” Delta as quoted in Guillén, and Ribera, IESE, page 4

[12] Beard, page 6

[13] Beard, page 4

[14] Guillén, and Ribera, IESE, page 4

[15] Guillén, and Ribera, IESE, page 14

[16] Guillén, and Ribera, IESE, page 9

[17] Alison Beard, “Mindfulness in the age of complexity,” Harvard Business Review, March 2014, page 5

[18] Guillén, and Ribera, IESE, page 10

[19] D. Goleman, R. Boyatzis, A. McKee, “Primal leadership: The hidden driver of great performance,” December 2001, Harvard Business Review

[20] Kendra Cherry, “IQ or EQ: Which One Is More Important?” about.com 29 March 2015 http://psychology.about.com/od/intelligence/fl/IQ-or-EQ-Which-One-Is-More-Important.htm

[21] Kendra Cherry, “IQ or EQ: Which One Is More Important?” about.com 29 March 2015 http://psychology.about.com/od/intelligence/fl/IQ-or-EQ-Which-One-Is-More-Important.htm

[22] Alison Beard, “Mindfulness in the age of complexity,” Harvard Business Review, March 2014, page 4

[23] Guillén, and Ribera, IESE, page 11

[24] Sharon Begley, “Rewiring you emotions,” 27 July 2013, Mindful.org http://www.mindful.org/rewiring-your-emotions/

[25] Begley, Pg 1

[26] Dan Harris, “10% Happier: how I tamed the voice in my head, reduced stress without losing my edge, and found self-help that actually works,” itbooks, 2014, page 228

[27] Harris, Page 228