Starting point – what land and water do we need?

Former Australian Government Chief Scientist, Alan Finkel, points out that the key challenge of hydrogen is ‘producing it’ and to do so ‘takes a lot of electricity and a good deal of water’.1

Unlike other fuels, hydrogen must be produced – either through electrolysis or from fossil fuel. Green hydrogen requires electrolysis production to be powered by renewable energy. It is a matter of debate whether this renewable energy needs to be co-located with the hydrogen project or if it can be derived from the grid to count as ‘green’.

Professor Finkel calculates that we would need:

- to produce 33 million tonnes of hydrogen for export to match 79 million tonnes of liquified natural gas Australia exported in the year to June 2020 (hydrogen has a superior mass energy density to LNG so the raw number is less)

- nearly 1000 gigawatts of capacity from solar to generate that hydrogen, or less (about 700 gigawatts) if wind energy is also included because of the superior capacity factor of wind.2

However, Professor Finkel sees this as ‘conceivable’ and since his article, one announced project alone – the Western Green Energy Hub in WA – is expected to cover 15,000 square kilometres, with a projected capacity of 50 gigawatt of upstream wind/solar equating to 3.5 million tonnes per annum of green hydrogen to be produced.

These two necessary elements for green hydrogen – land and water – bring us to first principles issues in any green hydrogen project. How do project proponents acquire the land that:

- has the right characteristics for solar or wind

- has good access to water

- can compete in economic terms against other uses – such as mining or agriculture

- is not in a place which local communities will object to

If we want hydrogen to have a grid stabilising role (ie, to absorb excess or supply more electricity to the grid based on demand), we can add to this list – ‘access to transmission lines’. However, this is not essential for a hydrogen project since hydrogen is a fuel and can be contained in cells or liquified form.

Identifying optimal characteristics

When we look at the requirements for a hydrogen project a few things stand out:

- Sunny locations are often in arid locations. Quite often, this will make water a challenge. Although arid coastal locations such as the Pilbara in Western Australia or parts of South Australia can be close to sea water, these are often areas of high environmental sensitivity and may be subject to native title rights. An Indigenous Land Use Agreement with traditional owners may be required.

- Windy locations are often at high altitude or coastal. High altitude can make water a challenge. Australia’s population is concentrated on the coast and coastal locations are more likely to attract community objections. But, offshore wind facilities can overcome this.

- Water suitable for irrigation will likely be best preserved for agriculture. Water in some states is subject to its own licensing and ownership regime – it would be necessary to acquire rights to the land and the water and this may be costly as well as likely to attract criticism for impact on food security.

- Similarly, rights to land will compete against other uses and can become too costly to acquire if the other uses have a higher economic benefit or existing rights (such as a pastoral or mining lease).

In relation to co-location of hydrogen projects with wind and solar, there are few points for debate.

- In light of the above observations, can we identify co-locations where there is suitable water available for hydrogen that is also adjacent to suitable locations for wind and solar generation?

- Is it sufficient for a green hydrogen project to buy green electricity from the grid (recognising that grid electricity is a mix of sources) or must a green hydrogen project be co-located with a dedicated wind or solar project to count as ‘green’?

- Finkel points out that hydrogen produces oxygen as a by-product and it would be ‘a bonus’ (but not fundamental) if this by-product could be used for an industrial purpose, for example to improve the efficiency of wastewater purification.3 Are there opportunities to co-locate with an industrial process for closed loop production, for example, by drawing waste water for the electrolysis and using the oxygen in that same location to treat the water?

- How can we create the legal architecture to permit concurrent uses of land?

Renewable Energy Zones in the NEM

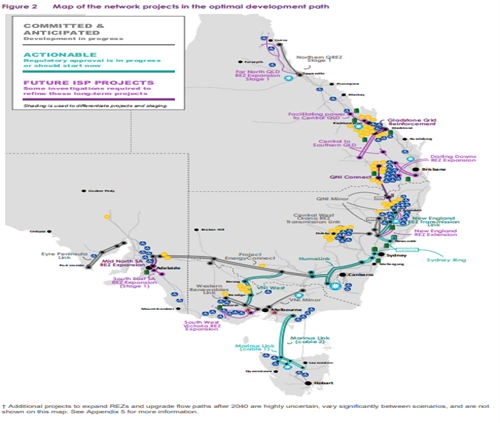

In the National Electricity Market, the question of ‘where’ in the case of large scale solar and wind projects has been in part answered by ‘the 2022 Integrated System Plan’ (ISP)4 and the Renewable Energy Zones (REZs). REZs promote the grouping of projects to support transmission infrastructure feasibility and provide investment and planning certainty. But, the picture is more complex and less certain for hydrogen because of the need for water and because it does not necessarily need to be near a transmission line. The images below show the present and future location of ISP projects and REZs.

‘Optimal Development Path’ – see ISP 2022, page 14, page 62

‘Future REZ Development’ – see ISP 2022 page 44

Diversification Leases in WA to permit Large Scale concurrent use

In WA, the State Government has introduced amendments to the Land Administration Act 1997 (WA) that creates a framework for competing and concurrent land use – the proposed amendments include a new category of lease of Crown Land called a ‘diversification lease’.5

The diversification lease is designed for large areas – broadscale use, similar to a pastoral lease. By contrast with a pastoral lease, the permitted use is flexible and may be set out in the lease as agreed by the parties. Permitted uses might include:

- renewable energy

- carbon farming

- aboriginal economic development and land management

- conservation purposes

- grazing livestock, horticulture or agriculture

- multiple concurrent uses

Under the new proposed legislation, existing pastoral lease holders may apply to convert their lease to a diversification lease (but it is not compulsory).

A diversification lease will not permit exclusive possession – it is designed for multiple concurrent uses and rights will co-exist with other rights and interests such as mining rights, pastoral rights and native title rights and interests.6 Although, some areas may be identified for ‘exclusivity’ – for example, areas with substantial structures and infrastructure such as solar panel arrays.

Diversification Leases and Native Title rights

Native rights and interests will not be extinguished by a diversification lease. A proposed lessee will need to address the appropriate future act process under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) before a diversification lease can be granted. This will most likely be negotiation of an Indigenous Land Use Agreement with native title holders or claimants and project proponents must meet the cost.

Diversification Lease and the Renewable Hydrogen Policy

The WA State Government has also just released a new policy framework for competing land use and hydrogen projects – ‘Renewable Hydrogen Policy: Consideration of highest and best use’7 and ‘Renewable Hydrogen Guidance: Land tenure for large scale renewable hydrogen projects’.8

Under the policy, if there is more than one project proponent with an interest in the same area of Crown land, the project proponents and any existing interest holders are encouraged to enter into a ‘Co-Existence Agreement’ to agree on how the projects and interests can co-exist. The policy gives examples of an agreement allocating separate tenure for areas for locations of significant infrastructure or possibly sequential use of the land.9

If a Co-Existence Agreement cannot be reached, the Ministerial Taskforce through a Senior Officers Group will carry out a ‘Highest and Best Use Assessment’.

The Highest and Best Use Assessment will consider various factors:

- alignment to Government Strategic Policy

- interaction of tenure types and potential for Co-existence

- financial capability

- engagement and record of previous engagement with Aboriginal people and social and economic benefits to Aboriginal people

Way Forward

In WA, land acquisition costs because of competing uses have been prohibitive to project viability. In other states, competing use has also been an issue – food security and preserving primary agricultural land for agricultural use is important.

At common law, a defining feature of a lease is that it grants the tenant exclusive use and occupation. Currently, leases for renewables projects will often include a reservation of rights to the landowner to permit concurrent farming use on some parts of the land, but this has limitations. In WA, the ‘diversification lease’ on Crown land will permit concurrent permitted uses. These are likely to play a leading role in freeing up more flexible use of land in WA.

The Western Australian Green Energy Hub is an excellent example of a location with all the right geographical features for green hydrogen co-located with wind and solar. The right geographical features for hydrogen projects co-located with wind and solar projects will often be in arid and remote coastal locations. It will be essential to engage fully and fairly with Aboriginal communities and to meet environmental standards for ongoing social licence as well as to meet statutory requirements. Relationship and engagement generally with the local community and others with existing rights and interests such as pastoralists and miners will be crucial to project success.

In WA, it will be interesting to see how the market develops around Co-Existence Agreements and Highest and Best Use Applications – in house teams and their counsel will be developing standards around these documents but many elements will be site specific and bespoke to the parties. Conduct and Compensation Agreements are already used between mining companies and pastoralists in Queensland and these may be a useful starting point for Co-Existence Agreements. Concepts in Interface Agreements (often used between stakeholders in other development contexts) may also be helpful.

The potential for co-location with industrial processes and closed circle production is exciting. Many more opportunities will become viable as the demand side for hydrogen grows.

For more information, please contact Hamilton Locke partner Margot King.

1Alan Finkel, ‘Getting to Zero: Australia’s Energy Transition’ (2021), Issue 81, Quarterly Essay, 66.

2Ibid, 66-67.

3Ibid, 61.

4Australian Energy Market Operator, Integrated System Plan for the National Electricity Market (June 2022) https://aemo.com.au/-/media/files/major-publications/isp/2022/2022-documents/2022-integrated-system-plan-isp.pdf?la=en

5Land and Public Works Legislation Amendment Bill 2022 (23 November 2022), s41 inserting ss92A to 92I into the principal act. The Minister’s power to grant a ‘diversification lease’ is in s92B and the conditions that may be included in a diversification lease are set out in 92C. For further information see: Land and Public Works Legislation Amendment Bill 2022 (www.wa.gov.au)

6Ibid, see s41 inserting s92D and 92E into the principal act.

7Government of Western Australia, Consideration of Highest and Best Use (December 2022), https://www.wa.gov.au/system/files/2022-12/221205_RenewableHydrogen-Policy_DIGITAL.pdf

8Government of Western Australia ‘Renewable Hydrogen Guidance: Land Tenure for Large Scale Renewable Hydrogen Projects’ (December 2022) https://www.wa.gov.au/system/files/2022-12/221205_RenewableHydrogen-Guidance_DIGITAL.pdf

9Ibid, 4.