Navigating capital controls

China is a major source of foreign direct investment into Australia. In 2017, $8.9 billion was invested in Australia by Chinese investors [1] and Australia is the second largest recipient of accumulated Chinese investment behind the US.[2] These transactions straddled a range of sectors, including mining, commercial real estate, transport infrastructure, health care and agribusiness. As the Chinese economy continues to grow, Chinese enterprises are still searching for acquisition or investment opportunities in Australia. This presents opportunities for Australian businesses looking for capital or buyers, particularly in industries where consumer demand in China is high and which align with the China’s strategic priorities.

There are various challenges in undertaking transactions with PRC investors or bidders. We will explore some of those challenges over a series of articles and offer practical suggestions on how to manage them. In this article, we turn our attention to the tightened capital controls that apply to PRC investors which have made it more difficult for Chinese entities to close deals overseas.

Capital controls – understanding the framework

The Chinese government imposes restrictions on Chinese nationals and enterprises making investments or acquiring interests in overseas entities and on the transfer of money out of China to fund these transactions. These controls on the outflow of capital and overseas direct investment (ODI) may affect the ability of Chinese enterprises to complete a transaction given that approval is often required for the investment or acquisition to be legally authorised in China (which is the Chinese investor’s risk) and for it to transfer funds out of China (which is the Australian entity’s risk). [3]

Prior to 2017, Chinese enterprises were encouraged to invest heavily around the globe as China experienced unprecedented growth. This investment activity saw China’s foreign currency reserves drop below internally acceptable levels and threated financial stability as many Chinese companies over-leveraged and undertook what President Xi Jinping described as ‘irrational’ global investments outside their core expertise, such as the acquisition of high-profile football clubs.

To address this issue, in 2017 the Chinese government significantly tightened the framework around capital controls and ODI restrictions. At a high level, there are three key features to this framework which are set out below:

1. Type of approval required: Chinese enterprises need approval at the provincial level from the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), Ministry of Commerce and State Authority Foreign Exchange for transactions under USD300m. If a transaction is more than USD300m, then approval from those same authorities will be required at the central government level. The most difficult approval to obtain is from the NDRC. Note that approval may also be required from the People’s Bank of China and state-owned enterprises also need approval from the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission.

2. Type of investment: proposed transactions are placed into three categories for the purposes of assessment by the relevant authorities: prohibited investments, which captures investments in industries such as entertainment, hotels, sports and tourism; encouraged investments in sectors related to the Belt and Road Initiative or other strategic industries such as mining, agriculture, advanced manufacturing and business services; and restricted investments or the ‘grey area’ which covers all other transactions.

3. Type of investor: additionally, the nature or type of the Chinese enterprise will influence the assessment of any application for approval, including assessments around:

-

whether the proposed investment is within the applicant’s core business;

-

whether the applicant is a state-owned enterprise (SOE), a private company with a track record or a fund. SOE’s are highly likely to receive approval (although note that approval will most likely be required in Australia by the Foreign Investment Review Board), whereas private companies (especially newly established companies with no track record) and limited partnership funds face greater scrutiny; and

-

the size of the applicant’s balance sheet and whether it needs to take on significant debt funding to complete the transaction.

Practical steps to navigate the capital controls

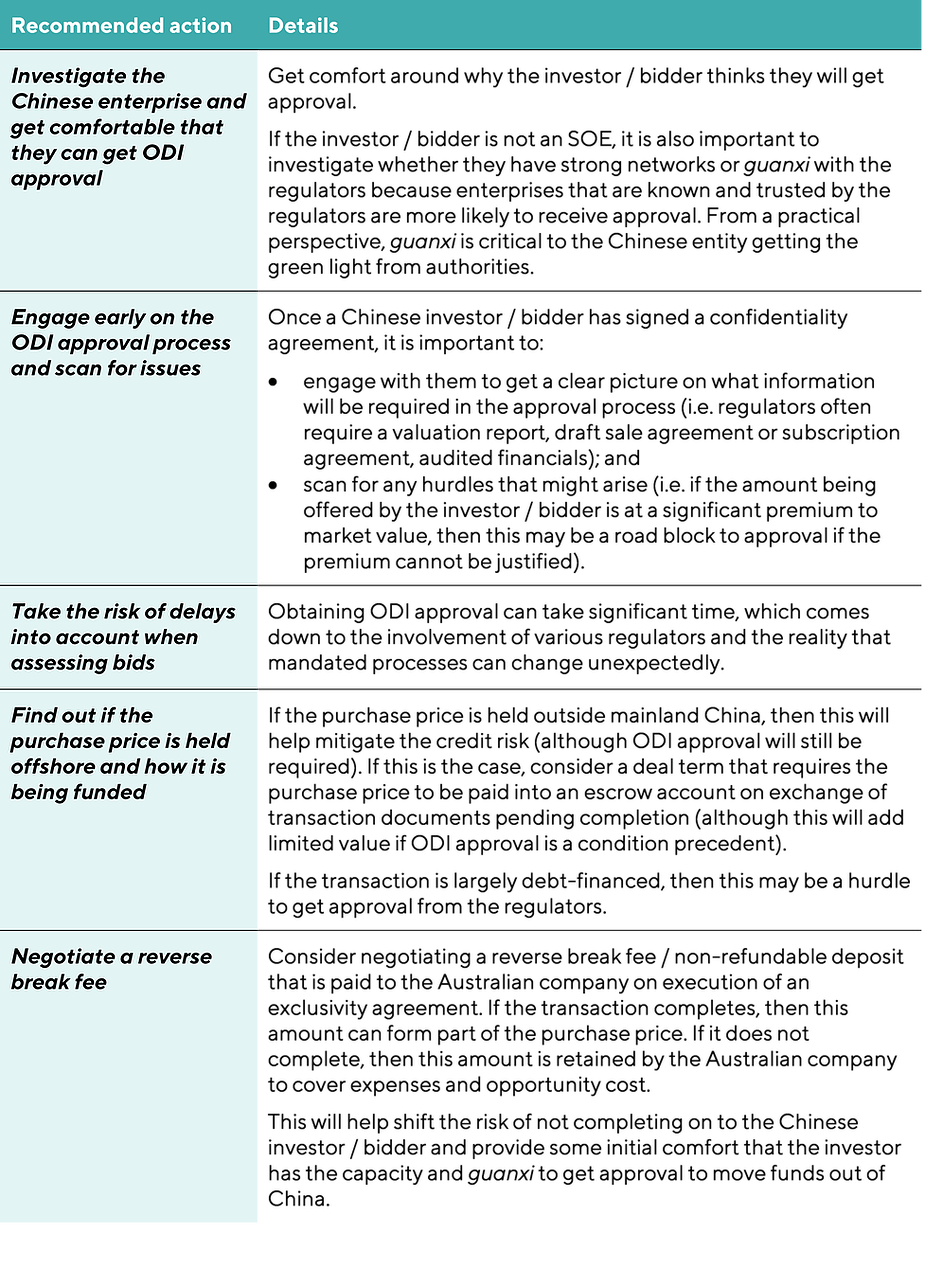

It is important for Australian companies contemplating a bid or investment by a Chinese entity to be on the front foot about the risk that the deal may not close if ODI approval cannot be obtained. The following steps are some practical pointers to help Australian companies assess and mitigate that risk and to facilitate the successful implementation of a deal with a Chinese entity:

Unfortunately, there is no way to eliminate the risk that ODI approval may not be granted – it is a regulatory hurdle that needs to be accepted and managed when dealing with PRC entities. Following the steps set out above should equip Australian companies with tools to assess and manage the risks involved in doing a transaction with a PRC entity. This will help to ensure that the Australian company is well placed to engage with Chinese capital in a positive and successful way.

About the authors

Written by Brent Delaney (Partner at Hamilton Locke) and Joshua Bell (Senior Associate at Hamilton Locke).

Brent and Josh have extensive experience in advising on Sino-foreign transactions, including acting for both Australian companies and PRC investors.

For a deeper dive by the Reserve Bank of Australia into the capital control regime, please see this link.

Sources

[1] Lisa Murray, ‘Chinese investment in Australia slumps 40 per cent’, Australian Financial Review, 7 October 2018, link

[2] KPMG, ‘Chinese investment in Australia remains strong despite global outflow slowdown’, 12 June 2018, link

[3] Note that for certain transactions the investor may only be required to file with the National Reform and Development Commission rather than apply for formal approval.