In a pivotal moment for Australia’s nascent offshore wind sector, the federal government recently rejected the state-owned Port of Hastings Corporation’s application for the Victorian Renewable Energy Terminal at the Port of Hastings in Western Port Bay, Victoria (Project).

The ‘clearly unacceptable’ application proposed constructing a terminal to serve as an installation port for offshore wind farm projects in Victoria. In her decision, the Minister for the Environment and Water, The Hon. Tanya Plibersek MP, cited concerns that the Project would breach both international environmental law under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands and federal laws under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act).

So why did the Port of Hastings application get rejected, and what lessons can other developers take away from the Project? In this article, we deep-dive into the implications of this decision, highlighting its significance in the broader context of Australia’s energy transition and the tension between managing impacts on the environment and the urgent need for renewable energy infrastructure.

The argument in favour of the Project: Renewable energy transition

Victoria’s ambitious and soon-to-be legislated targets for offshore wind energy – 2 GW by 2032, 4 GW by 2035, and 9 GW by 2040 – hinge on the development of suitable infrastructure for wind turbine assembly.

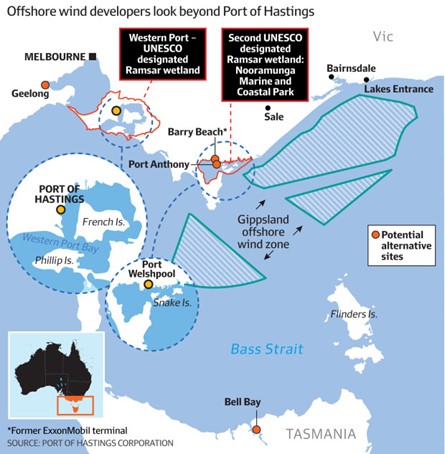

In September 2023, the Victorian government selected the Port of Hastings as the most suitable installation port for Victorian offshore wind farms. In its announcement, the Victorian government cited the following benefits of the Port of Hastings:

- its large areas of zoned land close to existing port precincts;

- its deep-water channels; and

- its proximity to proposed offshore wind projects off the coast of Gippsland.

Industry seemed to agree. Notably, Star of the South, Victoria’s most advanced offshore wind project, also identified the Port of Hastings as its preferred construction port.

The federal government’s decision to reject the Project is likely to delay the rollout of Victoria’s offshore wind and renewable energy transition. The construction of offshore wind infrastructure is central to developing Victoria’s offshore wind sector and is required to fill the supply gap caused by the retirement of coal-fired power stations.

The argument against the Project: ecological impact on Ramsar-protected wetlands

Minister Plibersek rejected the Project because of the ‘clearly unacceptable impacts on the ecological character of Ramsar wetlands protected’ under the EPBC Act. The Project entailed dredging and development activities in and around an internationally protected wetland, the Western Port Ramsar Wetland.

Under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Convention), signatories must establish and oversee a management framework to conserve Ramsar-designated wetlands. Among other things, wetlands are protected because of their ‘world-class’ carbon sequestration, which is up to 50 times more effective at sequestration than land-based forests.

Australia, one of the first nations to sign the Ramsar Convention, has 67 Ramsar wetlands, covering more than 8.3 million hectares (an area larger than Scotland).

Significantly, of the Project’s 146-hectare site, 121 hectares are situated within the protected wetland. The application proposed that up to 92 hectares of wetlands area would be dredged to enable ship access. The Project also involved unavoidable clearance of vegetation, seabed reclamation, significant pollution risk, and irreversible destruction to the habit of waterbirds, migratory birds, marine invertebrates and fish.

The Ramsar Convention is incorporated into Australian law under sections 16 to 17B of the EPBC Act. In making her assessment, Minister Plibersek identified that the government should not approve the application because of the significant impact it would have on the ecological character of this Ramsar wetland.

It is not the first time a development at the Western Port Bay has been rejected on account of the Ramsar Convention. In 2021, the Victorian Government rejected a proposed 300 metre long floating gas terminal because of unacceptable environmental impacts.

Next steps and alternative terminals

Although there is no appeal right (subject to an error of law), the Victorian government may submit an application for a revised or alternative project for assessment.

Meanwhile, the Star of the South is assessing Geelong (Victoria) and Bell Bay (Tasmania) as alternative construction ports. Tasmanian Energy Minister Nick Duigan has pitched Bell Bay as an ‘outstanding location for this type of infrastructure’, particularly to service construction and maintenance of Strait offshore wind farms in the Bass Straight, describing it. However, these ports are further away from the Gippsland declared offshore wind area and will increase the financial burden for a sector already facing significant cost pressures.

Alternatively, South Gippsland National Party MP Danny O’Brien has supported the use of the existing Barry’s Beach Marine Terminal for an offshore wind sector base. Barry’s Beach was established for the construction and maintenance of Bass Strait’s offshore gas platforms. However, using the Barry Beach terminals would require a massive investment in infrastructure, and Charles Rattray, CEO of Star of the South, stated that using this site was unlikely. Furthermore, Barry Beach terminal also sits in a Ramsar area – the Corner Inlet-Nooramunga wetlands. It may face similar difficulties in obtaining environmental approval.

Source: Financial Review

Four lessons from The Port of Hastings rejection

- The Port of Hastings rejection is a microcosm of broader tensions in renewable energy development – balancing environmental preservation with the urgent need for renewable energy infrastructure.

- This decision exemplifies that projects will not pass environment and planning laws simply because of the ‘renewable energy’ banner.

- The clash between environmental values and the urgency of renewable energy development will become increasingly prevalent in Australia’s burgeoning offshore wind sector and a balance will not be achieved without cooperation between all levels of Australian government.

- Offshore wind proponents must thoroughly understand the regulatory regime and strategically plan their projects.

Get in touch

Hamilton Locke is dedicated to helping clients navigate these complex challenges adeptly. With extensive experience in the new energy sector, we advise across the energy project life cycle – from project development, grid connection, financing, construction, including the buying and selling of development and operating projects.

Our previous articles discussed the offshore wind regulatory regime (including the Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act 2021 (Cth) (OEI Act) and the EPBC Act), the relevance of native title, and other offshore wind farm site considerations.

Our latest New Energy Quarterly – the Way of Water features extensive analysis on the development of Australia’s offshore wind sector.

To stay informed on the evolving challenges and opportunities in the renewable energy sector, please reach out to our experts Matt Baumgurtel or Amelia Prokuda.

Matt Baumgurtel leads the New Energy sector team at Hamilton Locke which specialises in renewable energy, energy storage and hydrogen projects and transactions as part of the firm’s Energy, Resources, Construction and Infrastructure practice. The New Energy sector team has market-leading experience with hydrogen developments across Australian jurisdictions and are up to date with the latest national and international policy developments in the constantly evolving, dynamic hydrogen value chain.

Amelia Prokuda has extensive experience working on matters relating to town planning, infrastructure and environmental law. She has deep expertise acting for a range of clients including property developers, commercial clients and state and local governments. Amelia often advises clients on issues relating to a diverse range of property, resources and infrastructure projects. She has experience advising clients on complex issues involving statutory interpretation, development applications, infrastructure charging regimes, development compliance programs, due diligence and environmental compliance and liability.

References:

Financial Review, Victoria suggests wind power before wetlands

The Sydney Morning Herald, Victoria’s energy transition in strife as ‘essential’ offshore wind hub refused.

Financial Review, ‘We wouldn’t do it for a coal mine’: Libs back Plibersek in wind fight

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, ‘Statement of Reasons for a Decision that the Action is Clearly Unacceptable under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999’